| «back to publications | ||||

SPANISH SUMMARYby With a Foreword by |

||||

|

||||

|

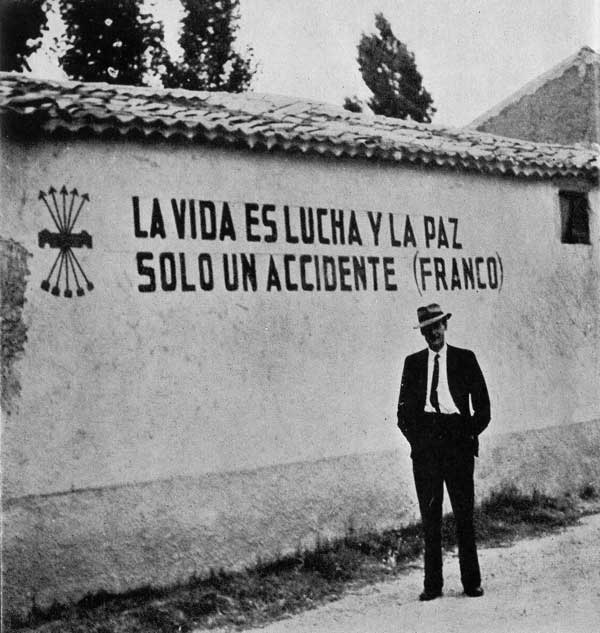

On the road to Madrid. The slogan, quoting General Franco, reads 'Life is a battle and peace only an accident'. The hat (the author's only 'disguise' in Spain) was a local purchase.

|

||||

|

CHRONOLOGY»top

| 201 B.C. | Roman Armies enter Spain. |

| A.D. 406. | First Barbarian invasion. |

| 586-701. | Visigothic King adopts Catholicism. |

| 711. | First Moorish invasion. |

| 1250. | Spain, except for Granada and a few southern ports, free from Moorish rule. |

| 1479. | Union of Spain ender Castile and Aragon. |

| 1480. | Inquisition established. |

| 1492. | Christopher Columbus discovers America. Granada captured: Reconquest complete. First expulsion of Jews. |

| 1502. | First expulsion of Moors. |

| 1516. | A Hapsburg, later the Emperor Charles V, becomes Charles I of Spain. |

| 1520. | Rebellion of municipalities in Castile. |

| 1571. | Spanish colonists found Manila. |

| 1588. | Defeat of Spanish Armada by England. |

| 1610. | Second expulsion of Moors. |

| 1700. | Death of last Hapsburg King and accession of the Bourbons. |

| 1701-13. | War of the Spanish Succession. |

| 1759. | Accession of Charles III. |

| 1793. | Spain joins the coalition against Republican France. |

| 1808. | Beginning of Peninsular War. Joseph Bonaparte becomes King. |

| 1810. | Meeting of first united Parliament. |

| 1812. | First democratic constitution. |

| 1814. | French expelled. Bourbon restoration. |

| 1820. | Military revolt against King. |

| 1823. | King restored by French. |

| 1834-40. | First Carlist War. |

| 1845. | New Constitution. |

| 1868. | Revolution expels Queen Isabella. |

| 1869. | Liberal Constitution drawn up by Parliament. |

| 1869-76. | Second Carlist War. |

| 1873. | First Spanish Republic. |

| 1874. | Military coup restores Bourbons. |

| 1876. | New Constitution. |

| 1898-9. | War with the United States. Loss of last of transatlantic and Pacific possessions. |

| 1909. | First major military disaster in Morocco. Riots in Barcelona. |

| 1921. | Second major nilitary disaster in Morocco. |

| 1923. | Primo de Rivera becomes dictator. |

| 1927. | Morocco pacified. |

| 1930. | Primo de Rivera resigns. |

| 1931. | March. Abdication of King Alphonso. Second Republic proclaimed. April. General Election. |

| 1932. | Sanjurjo rebellion. |

| 1933. | General election. Right-wing coalition victory. |

| 1934. | Popular revolts. Asturias rising. |

| 1936. | February. General election. Popular Front victory. July 13. Murder of Calvo Sotelo. July 17/18. Army rebels. |

| 1936. | August. France appeals for non-intervention. Britain bans exports of arms to Spain. September. Fall of Irun. Siege of Madrid begins. Non-Intervention Committee meets. October. Franco declared Chief of State by rebel ofmicers' committee. British Labour Party calls for abolition of non-intervention. November. Germans and Italians recognize Franco. December. First Italian regular troops land. |

| 1937. | March. Government victory at Guadalajara. April. Guernica bombed. Franco amalgamates Falange and other right-wing parties. May. Deutschland shells Ahmeria. June. Rebels take Bilbao. August. Rebels relieve Oviedo. |

| 1938. | January. Government takes Teruel. March. Rebels enter Catalonia. September. International Brigade disbanded. |

| 1939. | January. Rebels take Barcelona. February. Great Britain and France recognize Franco. March 5. Government leaves Madrid for France. April. Non-Intervention Committee dissolved. May. Franco holds Victory parade in Madrid. July. France sends Spanish gold and other assets back to Spain. September. Second World War begins. Spaio declares herself neutral. |

| 1940. | June 12. Spain becomes "non-belligerent". September. Franco and Suner meet Hitler. Suner goes to Rome. December. Spain suppresses international control in Tangier and expels British and French officials. |

| 1941. | January. Britain sends wheat to Spain. February. Franco meets Mussolini and Pétain. July. Franco announces that Blue Division has left for Russia. British Government sends petrol to Spain. |

| 1942. | September. Suner deposed from Foreign Ministry. |

| 1943. | July. More Spanish troops leave for Russian front. August. Franco sends representative to French Committee of Liberation. November. 3,000 Blue Division troops withdrawn from Russian front. December. 7,000 Blue Division troops withdrawn. |

| 1944. | January. U.S.A. complains of unneutral acts on part of Spain. Suspends oil supplies. |

| 1945. | August. Republican Parliament meets in Mexico. Potsdam Declaration excludes Spain from participation in U.N. |

| 1946. | February. French-Spanish frontier closed. March. Tripartite Declaration of America, France and Britain condemning the Franco republic. April. Poland raises Spanish question in Security Council. December. United Nations agree to withdraw Ambassadors. |

| 1947. | February. Socialist becomes Republican Prime Minister. April. Anglo-Spanish Monetary Agreement. |

My friend "Ramon" was a mild and unobtrusive-looking person. He was very different from the popular idea of a resistance chief. But his power of leadership, his patience, and his courage were immense, He had been through the civil war, was sentenced to death by Franco, and had spent years in Spanish prisons. It was there that he began his work with the underground. He was my guide and companion throughout my journey.

Politically, "Ramon" was a moderate. In an atmosphere of bitterness and hatred, from which he had often personally suffered, he preserved a calm and liberal outlook and a firm dislike of extremism in any form. But when, in his company, I visited and talked with leaders of different political groups and parties, he made no comment and kept his own views secret.

Shortly before I left him to recross the Pyrenees, we had a long discussion. In his secret hiding place, the room which had served him as his headquarters since the last of his frequent "changes of address", we talked through the summer night and into the early hours of my last morning inside Spain. Friends kept watch for the police below.

We began far back in Spanish history. As he spoke of old problems, old triumphs, and old despairs, gradually a pattern, a thread of continuity emerged. He let me draw my own parallels with the problems of the present day. Strong though my admiration for him and for his cause had been before, he left me now with a new feeling of sympathy and comprehension. Many of his remarks and observations then and at other times during our journey have stayed in my memory. I was often reminded of them as I wrote the various sections of this book.

To him and to my other friends of the Spanish resistance movement, I am indebted for the great risks they took on my behalf, and for the information which they gave me, while I was their guest. I am also grateful for the reports that they have sent me since I left Spain.

For background information, I found the books listed on Page 96 particularly helpful.

F. N-B

London, 1948

FOREWORD

by

LADY MEGAN LLOYD GEORGE, M.P.

THE central facts of the Spanish Civil War, so forcibly contested in Parliament and on the public platform in this country before 1939, have now become generally accepted. No one can doubt any longer that from the earliest days of the Civil War, Franco was dependent on Mussolini and Hitler for his military success, or that the Democratic countries made a definite contribution to his victory. By their policy of non intervention, they prevented the popularly elected Republican Government from obtaining the supplies to which they were legally entitled, and without which they could not hope to win. Nor can anyone who studies the evidence with any degree of impartiality doubt that while this cruel farce of non intervention was being played out, the Axis Powers were able to stage an effective dress rehearsal for the world war that was to follow.

All this has now become part of the tragic history of appeasement. The two senior partners of the Triumvirate have gone to their own places. Franco remains. The United Nations have passed a resolution disapproving of him. They have even gone so far as to brand him as a pariah. Is that really all we can do by way of moral condemnation, of political ostracism, of Franco's regime? The world certainly cannot afford more bloodshed at the present time. Neither can it afford the example of triumphant Fascism in Spain. The process of denazification to which we rightly attach so much importance will be far from complete while Franco continues to govern Spain. There is a real danger that we may drift into a tacit acceptance of this survival of Fascism in Europe.

Francis Noel-Baker has given us in this admirable book a calm and well-informed account of the Civil War and of the present political position in Spain. It is only by keeping public opinion here and elsewhere constantly aware of the facts of the situation that we can hope to shame the Democracies into further action.

MEGAN LLOYD GEORGE.

1. DEBATE IN THE HOUSE»top

ONE evening in 1946 the House of Commons was discussing Spain. A Minister of the Crown was defending himself from fierce criticism, which came mostly from his own supporters. What had become, they asked, of their election pledge that a Labour Government in Britain would work for the removal of the last vestiges of Fascism in Europe, and the restoration of democracy to Spain? The Minister replied, in effect, that though the Government detested General Franco, and hoped that the Spanish democrats would overthrow him, there was little positive help that we could give them. At this, Conservative M.P.s on the benches opposite protested at the mere idea of interference in the internal affairs of a foreign country, and angrily demanded what business it 'was of Britain's what kind of Government ruled Spain.

The members who spoke in the debate did so with great conviction. Some had an intimate knowledge of the facts. Others were less well-informed. I myself felt strongly that the Government policy was weak, and the Tory members dangerously wrong. But my knowledge of the Spanish problem was not extensive. It consisted principally of the belief that dictatorship of any kind was evil; of memories (at second hand) of Fascist and Nazi intervention in the Civil War; of recollections of Franco's support of Hitler in the years that followed; and of information from various Spanish friends in exile. When a colleague suggested to me that this was an inadequate basis for strong views about our policy towards Spain, I began to wonder what more I could do to understand the Spanish problem and its implications.

There followed a search for further information. Background material was sifted, current reports studied; contacts established with Spanish Republican leaders; visits made to democratic groups in exile. At the same time, preparations of another kind were quietly arranged.

On a dark summer night, some weeks later, the sequel to these preparations began.

The plan of action had been settled well in advance. I had had my "briefing" in Paris and there had been discussions about the programme and the route. With guides from the Republican underground to lead me, I was to slip across the Pyrenees without arousing the suspicions of the frontier guards. As soon as I was safely inside Spain. I was to contact the chief of one of the clandestine organizations, and, with his help, travel across the country to the three main centres of political activity—Barcelona, Bilbao and Madrid. In these cities I would meet the representatives and leaders of all the different democratic groups and parties, the heads of resistance movements, and the committees which they had set up to co-ordinate the work of all the active opponents of the Franco régime.

My journey and my identity while I was in the country were closely guarded secrets. Until I had left, only five men—three in Spain and two abroad—knew who and where I was. When, after my arrival back in France, the story broke, the Spanish Government was taken completely by surprise. A bribe of 200,000 pesetas (about £4,500) was offered to anyone who would give information about how I had crossed the frontier. It was never claimed.

Later, several stories (all equally fantastic) were circulated about my journey. It was alleged, for example, that I had travelled on a false passport; that I was in disguise; that the Spanish authorities had had me followed all the time. For some months the Spanish radio and Press honoured me with a series of violent denunciations. But, to this day, my movement and my contacts during August 1946 are an unsolved mystery at police headquarters in Madrid.

I make no apology for my secret visit to Spain. In a country where every political movement except the Falange is illegal, there was no other way in which I, a Labour M.P., could have met and talked with opposition leaders. It was their safety, not mine, which would have been in peril had I travelled openly and subject to the supervision of the political police. Indeed, not one of them would have dared to meet me had they not been certain that my identity and presence were unknown. Furthermore, with memories of the conducted tours of British politicians in Hitler's Germany before the war, I had my doubts about how much an official visitor might be allowed to see in Franco Spain.

Nevertheless, as soon as I recrossed the frontier, I addressed myself to General Franco's Ambassador in London. It might be argued, I wrote, that as the guest of the underground, I had got an incomplete picture of the situation in his country. Therefore, if his Government would guarantee me the same freedom of movement and contact as I had been granted by my former hosts, I should be grateful for a visa to return. I was not altogether surprised that he made no reply.

This clandestine visit to Spain had several useful results. First, I saw with my own eyes the extent of the resistance movement, and discussed with its leaders their methods and their views (see appendix 5). For a very short time I shared their difficulties and dangers, and could afterwards understand more vividly what it means to live as the citizen of a post-war fascist state. Second, I established direct and permanent contacts with many people in Catalonia, in the Basque country and in Madrid, and the reports they now send me are of great value in keeping me informed and up to date. Third, my journey in itself did, I believe, do something to raise the morale of the resistance movement and its leaders who, at the time of my arrival, were feeling particularly isolated and abandoned by their foreign friends. From the Press and radio they learned who I was as soon as I returned to France—the immediate publication of the news being one of the few conditions stipulated by my hosts.

This book, however, is not the story of a brief underground journey in Spain. The details of those adventures (there were a few, although our programme was carried out to time and without a single serious hitch) cannot yet be told. Too many of my companions and the people whom I met there are still in danger of their lives. They will continue to work and to organize—and if the need should come again, to fight—for the liberation of their country and the restoration of democracy to Spain. But until their struggle has been won and they are free, the secrecy of the underground is their most precious weapon.

It is my belief that their struggle, its causes, and its aims, are of great importance to Great Britain and the British people. That is my reason for putting on record now the results of the investigation (of which my journey was the briefest, though the most vivid, part) which I started after a debate in the House of Commons. This is not an "expert" book. My aim is very simple: to set down some of the more important facts; to put the immediate issues into focus; and to draw my own conclusions.

Spanish fascism is one of the still-unsolved problems of the Second World War. Already, in the past three years, it has been a source of mischief and misunderstanding among the nations. Alas, it is not the only cause of discord on the continent of Europe. But, as I shall try to show, with goodwill and effort a solution could be found. In that solution I believe that our country has both an obligation, and an interest, to play a big part.

2. THE BACKGROUND - I»top

IT is hard to follow contemporary Spanish politics (still harder to consider future changes) without some knowledge of the history of Spain. Not of dates and kings and battles, but of the main phases of development through which successive generations of Spaniards have passed. Modern difficulties, and the efforts and aspirations of those who seek to overcome them, can be seen in perspective only against the background of centuries of national, imperial, religious, social and economic struggle and upheaval.

Very early in a study of Spanish history one is struck by the way in which the same situations, the same problems, and the same failures to solve them, repeat themselves time and time again—particularly in the last 200 years. It would be hard to find elsewhere the same constant, indeed monotonous repetition. Each time a crisis is reached in the struggle for political liberty, social progress or economic reform, there are always some new factors, but the basic issues change very little through the years. Therefore from the happenings of the past a good deal can be learnt which applies to the present and the future.

Geographically, Spain is isolated from her neighbours. The great mountain barrier of the Pyrenees kept her aloof from the main currents of continental development. She followed a pattern of her own. Her proximity to North Africa (with which in prehistoric times she was linked by land), and the long years of Moorish occupation, left an indelible mark on all her later progress. Spain, from the Middle Ages onwards, was out of step with the rest of Europe. She is still out of step today.

The origins of the people who now inhabit Spain are still obscure. There are various conflicting theories about when and whence they came One thing is certain: they are now a mixture of many races, upon whom many different civilizations have been imposed. Although, with one exception, race consciousness has now disappeared in Spain, and though proximity and long association has given all Spaniards many common memories and many similar characteristics, unity among them is still not permanently established. The problems of regionalism, local autonomy and centralization are discussed later in this book. But in at least one instance, the Basque provinces, modern "centrifugal" tendencies are, in origin, racial and ethnological as well as political and economic.

Spain was first united, and her detailed history begins, with the arrival of Roman armies 21 centuries ago. The Roman occupation lasted for 600 years. It was the most prosperous and peaceful period that Spain has ever known. The fact that today, in the 20th century, Spain is only able to support less than one-half the population of Roman times, is a grim and striking comment on everything that has happened since. The Romans seem to have been the only rulers who were able to impose a central administration which could be reconciled with regional and local interests, which guaranteed a stable government, and which enabled Spanish economy to flourish. Great areas which are now desert were then rich and fertile agricultural lands. Mineral resources were as fully exploited as the techniques and equipment of the times allowed. A great literary and artistic civilization developed. The modern language of Spain was born.

Although the Roman occupation began as an imperial and colonizing process, the people of Spain very soon ceased to consider themselves, or to be considered, as the subjects of foreign Power. The country took two centuries to conquer (in the mountains of the north and north-west the conquest was never completed), but a century after that the Emperor of Rome (Trajan, who came to the throne in A.D. 98) was a Spaniard by birth, and a line of Spanish emperors succeeded him, Many of the leading writers of the "silver age" of Roman literature came from Spain; and long before the decline of Roman power began she had become as much a "latin" country as Italy herself.

During the Barbarian invasions which followed—of Vandals, and Visigoths from across the Pyrenees—the course of events in Spain was much the same as in other former Roman provinces. It was a Visigothic King who introduced the Christian, and a little later the Catholic, religion. But the unity and the economic stability of the country were destroyed, and her prosperity and population gradually declined. Then, in the 8th century, came another invasion from the South.

The Arabs, Syrians and Berbers, who formed the spearhead of the first Moorish armies, were the forerunners of a new civilization which lasted in some parts of Spain for the next 800 years. It was the arrival of the Moors which finally took Spain out of her European background, broke the continuity of her development, and left her, in the late 15th century, without a parallel in Western Europe. Most of her problems when the Moorish occupation ended were entirely different from those of her neighbours at that time. Others, they had already faced and overcome.

When the Caliphs ruled at Cordoba, Spain became as important a centre of the Moslem world as Baghdad. The new civilization and culture (like the Moorish armies) were superior to those which they replaced. Their roots went very deep down into Spanish soil. Certainly it was an oriental civilization. It had little in common with Spain's past or with her future. But though the leaders had Arab names, though their origins, their methods and their ideals could be traced back to the deserts of the Middle East, yet they soon ceased to be the foreign rulers of a subject people. The Moorish occupation left an imprint which it took long years of fighting, persecution, and eventually mass expulsions, to remove. And those expulsions—of Moslem or recently reconverted Spanish "Moors"—only ended in the beginning of the 17th century. With their departure, Spain lost some of the economically most important sections of her population, and there are those who say that Spanish agriculture has not yet recovered.

The Christian reconquest is a period which has been enshrined in Spanish literature and tradition. Like all crusades, it evoked great enthusiasms and great intolerance. It sowed the seeds of many future problems. There is a theory that the people of Spain have always been (and therefore always will be) intolerant and unable to compromise. This is not by any means supported by all the facts of history. Spain under the Moors had been the home of three religions—Moslem, Christian and Jewish. There were, of course, advantages in adopting the religion of the rulers. But there were periods of great toleration, when Moslems and Christians actually shared the same place of worship.

Later, in the dominions of the Christian Kings in Northern Spain, Moslems and Jews in the 11th, 12th and 13th centuries were perhaps more secure and respected than religious minorities anywhere else in Europe at that time. But the reconquest did destroy religious toleration. It also caused great material destruction. Among other things, many of the Moorish irrigation schemes in Southern Spain have never been rebuilt.

The war began, locally and spasmodically, in the Christian provinces and kingdoms of the north. For many years some of these were still nominally under Moorish suzereignty, and unity of purpose between them took a long struggle to achieve. Those were days when the modern conception of nationalism was still unknown. The great unifying force was the Catholic religion. In spirit, it was not so much a war of liberation fought by Spaniards against a foreign occupation, but a war of religion fought by Christian princes and their subjects against the infidels of the South. It can only be seen in true per-spective if Spain is looked at as a frontier, and a point of impact, between Eastern and Islamic, and Western and Christian civilizations.

For this reason, and because the fight against Islam lasted for so long, catholicism and the Catholic Church became more closely identified with the national purpose in Spain than anywhere else in the world. The first origins of Spanish clericalism and anti-clericalism are to be found in the wars against the Moors. Without the Church the wars might never have been won. But without those wars to fight the Church would never have achieved its dominant position in modern Spain. During the centuries of fighting, as the tide of Islam gradually receded, the crusading spirit became a part of the national character of the Spaniards. Under the influence of the Catholic clergy, grew up the powerful belief that all wars are ideological and all differences of opinion crimes.

Early in the 11th century, when the tide had already began to turn against the Moors, the various independent Christian States of the northern fringes of Spain began the process of unification. The ruler of Navarre, who later acquired the kingdoms of Castile and Leon, was the first to claim the title "King of the Spains". A century later a King of Aragon achieved the unification of another block of states, styling himself ''Emperor'' of Spain, though after his death his dominions again disintegrated. By the year 1250 the whole country, with the exception of the Moslem province of Granada and a few ports round the coast, was under Christian rule.

At this stage the reconquest left the country roughly divided into two. In the West was a loose agglomeration of peoples and provinces who owed allegiance to the King of Castile. The East, parts of which had close ties with France and Mediterranean Europe, centred round the Kingdom of Argon. It was not till 1479 that Spain was nominally united.

The joint reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, which began in that year, is generally taken as the starting point in the history of Spain as a modern European nation. But though the first central administration dates from then, and although all Spain now recognized one royal house, real political unity was still a long way off. The kings still ruled not one but many kingdoms. Each had its own local laws and customs. There were separate parliaments, civil services, armies and systems of taxation. There was no such thing as a Spanish subject: a citizen of Barcelona was as much a foreigner in Seville as in London or Rome.

As before, the one great unifying force which exercised its rights alike in every part and province of the country was the Catholic Church. It was the only truly national institution. For all its doctrine of universality, it was first and foremost the Church of Spain. For this reason a breach between the King and the clergy was impossible in Spain. But breaches between Spanish rulers and the Pope in Rome were not only possible, but frequent. Always, the reason for conflict was the eagerness of kings to preserve unchallenged the unity of Church and State.

The unique position of the Church naturally gave it not only spiritual and political authority, but great material power. As early as the 12th century Church landowners enjoyed special exemptions from taxation. In many provinces they were granted important legal and judicial privileges as well. The first big organized political and social task entrusted to the Church after the reconquest, followed the establishment of the Inquisition in 1480. Originally set up to supervise the religious behaviour of converted Jews, its jurisdiction was extended some years later to all Christian subjects of the Spanish King.

Its origin and its early work (it was the Inquisition which urged the big expulsions of both Jews and Moors) explain its natural transition from being the guardian of the Catholic religion against heresy, to becoming the guardian (officially recognized as part of the machinery of Government) of the Catholic state against subversion of all kinds. When the expulsions had been completed, and after a brief period of moderation, the Inquisition turned all its energy and resources against the new doubts and doctrines that were sweeping Europe. From that time on, Spain was sealed against the subversive influence of the Renaissance. One more barrier had been set up to isolate her from her European neighbours.

Meanwhile, however, great events were taking place across the seas. In 1492 (the same year that the last Moorish outpost fell) Christopher Columbus, on a mission for the Court of Spain, had crossed the Atlantic and discovered the West Indies. Next year, the first permanent Spanish settlement was established in the New World. Less than thirty years after that, the whole of Mexico had been con-quered and pacified, most of Central and South America penetrated, and bases established throughout the West Indian islands. By 1571 Spanish colonizers had crossed the Pacific Ocean and established the town of Manila in the Philippines. In less than a hundred years Spain had become the World's greatest Empire. It was not till more than a century later that the first permanent British transatlantic colony was founded.

Today, when that Empire is only a memory, and a few tiny scattered colonies are all that remain of Spain's overseas possessions, it has become the fashion to condemn outright the whole process of her imperial expansion. Certainly barbarous and brutal methods were used. The native South American civilizations were obliterated; in some areas the native populations were wiped out. But those were times when massacre and annihilation were the normal practice in wars of conquest—particularly when Europeans were fighting an enemy not only foreign but heathen as well. The numbers of Spanish troops employed in the early stages were fantastically small. As military ventures, their campaigns in Central and South America are without parallel in daring and brilliant execution. And even from the social, humanitarian point of view, there were redeeming features. The missionary purpose of the Spanish empire builders was not all humbug. Some of the strongest denunciations of cruelty and oppression came from the Spanish clergy overseas. The Spanish Catholic civilization which still dominates great areas of the New World has many qualities and achievements to its credit. Not least among them (and one which the later British settlers cannot claim) is the absence of the colour bar.

3. THE BACKGROUND - II»top

DURING the period of imperial conquest, important changes were taking place inside Spain. Less than half the country was effectively involved in the work of colonization and the transatlantic commerce that followed in its wake. For many years citizens of the Eastern provinces were excluded, and until as late as 1778 (less than 50 years before Spain lost every one of her possessions on the South American continent) all trade with the New World had to pass through the west coast port of Seville.

Meanwhile, the crown was gradually establishing itself as the centre of all authority. By the reign of Philip II (husband of our own Mary Tudor) this centralization had reached the stage where, with a few local exceptions, almost every detail of administration had to receive the personal attention of the king. A great State bureaucracy grew up around him. For the next two centuries the well-being of the Spanish people depended very largely on the personal ability of the occupant of the throne. That ability was not always equal to its tasks. It was the monarchs, too, who drew Spain into a series of foreign entanglements in Europe which made heavy calls on her manpower and resources and brought her little benefit in return.

There was, for example, no good political, strategic or economic reason for the Spanish occupation of the Netherlands. They had become a possession of the Spanish crown for purely dynastic reasons when a Hapsburg prince (Philip's predecessor) inherited the Spanish throne. They remained Spanish for as long as Spain could maintain bitterly hated armies of occupation. As soon as Dutch resistance and foreign intervention forced then to withdraw, the unnatural union ended. From a Spanish point of view, many of the other entanglements in Europe which followed, when that same Hapsburg prince became the Emperor Charles V. were as unnatural and as damaging to Spain as her fruitless campaigns in the Low Countries.

At home, the growth of the personal authority of the kings steadily widened the gap between the Spanish people and their rulers. In other European countries, notably England, this was the period when the middle classes were growing up. Through their Parliament, they began to challenge royal prerogative and to win a series of important victories for the principle of government by consent—if not the consent of the people, at least of the bourgeoisie. In most of Spain, however, there was no effective middle class. The expulsions of the Jews (and, to a lesser extent, of the remaining Moors) had seriously depleted the bourgeoisie. The royal policy of centralization which followed gradually diminished the power of representative local institutions. Above all, there was no central rallying place for popular forces—no focal point for opposition to the court.

In many provinces and towns, local democracy had developed early in Spain. In several cities municipal governments can be directly traced to Roman times and the origin of the Basque Parliament is lost in pre-history. The first parliaments—of Leon and Aragon—met in the late 11th century, nearly 200 years before the "Model" Parliament in England. But the municipalities, by their nature, were not often capable of united action, though they did —in Castile in 1520—lead the first big rebellion against royal absolutism. The parliaments too remained separate and disunited. If the unification of the nation under one crown had been followed by the unification of the parliaments of the various component states, constitutional monarchy might have developed as it did in Britain. But it was not till as late as 1810, after years of upheaval, war and foreign intervention, that a united Spanish Parliament first met.

As the power of the king—and, in the reigns of weak monarchs, of the court—increased, the cleavage between subjects and rulers became even wider. On the one side was a small minority of enormously powerful and wealthy aristocrats, landowners and prelates. On the other, a vast majority of poverty-stricken, oppressed peasants, whose voice was only heard in times of rebellion and disintegration. On the fringes of the kingdom, where local industry and foreign trade built up mercantile communities, a new middle class did gradually grow up. But throughout vast areas of central and southern Spain, society has remained almost mediaeval to this day. Stifled by disunity and royal power at a time when it was just developing elsewhere in Europe, the will of the people is a very recent force in Spain.

Nevertheless, there were, in the 16th and 17th centuries, at least some limitations on the power of the King inside Spain. The strangled voices of municipalities and provincial parliaments, and the threat of revolt and disintegration, could not always be ignored. In the Empire, however, personal government was unhampered by these things. The despotism of viceroys and prelates was absolute. Centralization was complete. Policy and administration depended exclusively on the King's instructions. The wars of independence by which the Spanish colonies eventually won their freedom had many causes. But it is a fair comment to say that if constitutional government had been able to develop at home during the period of Spanish consolidation overseas, Spain might still today have had a transatlantic Empire.

In the event, she remained the world's leading Power until early in the 17th century. The beginning of her decline is often dated from the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588. Though the Empire itself survived for many years, that operation did mark the end of Spanish naval supremacy, and the rise of England as her successor on the sea.

Meanwhile, however, there were many internal causes of decay. Spanish agriculture had never properly recovered from the expulsion of the Moors. Oppressive and antiquated systems of land tenure imposed not only low standards of living on the peasants, but a very low level of production. The centralization of government, and the growth of the royal bureaucracy, stifled political and local freedoms, and at the same time fostered incompetence and corruption. Economically, the growth of the Empire had weakened rather than strengthened Spain. Short-sighted restrictions and the absence of a consistent and practical economic policy deprived her of much of the prosperity which could have resulted from her transatlantic trade. The great influx of precious metals—the gold and silver on which English pirates cast such jealous eyes—itself helped to produce inflation and a rise of prices. Later, financial crisis was aggravated by royal decisions to debase the coinage. In the middle of the 17th century Spain, discoverer of Eldorado, had to abandon the gold and silver standard.

To these difficulties were added revolts and insurrections inside the kingdom, and a long period of entanglement in the conflicts of Central and Western Europe. During a great part of the 17th and 18th centuries the Spanish people were fighting, and being fought, for causes in which they themselves had little interest. Gradually their resistance and resources were worn away. The crown of Spain lost all its foreign dominions on the continent, and itself (ironically enough) became the inheritance of a Bourbon prince. He was a grandson of Louis XIV, King of France, the nation which had been Spain's chief continental enemy. His accession, in 1700, gave rise to a new series of conflicts—the war of the Spanish succession—in which Spain became more and more a passive victim.

Writing in 1946 a Spanish author commented that in the last 300 years the Spaniards have been allowed to play only a small part in the history of their country. Dynastic ambitions and foreign intervention dragged Spain hither and thither between warring foreign States. Often Spain was the immediate cause of conflict. Almost always, whether her "allies" were victorious or not, she was the loser.

As before, policy and government still depended exclusively on the persons of the King and his advisers. In the second half of the 18th century, a progressive monarch, with a new conception of benevolent despotism and a flair for choosing able ministers, was responsible for a period of enlightenment and revival. In King Charles III's reign Spain made great efforts to catch up the rest of 18th-century Europe. But despite big reforms in the administration, despite an economic revival, and despite the expulsion of the Jesuits and a new moderation imposed on the Inquisition (the burning of heretics was stopped, and even prosecutions for heresy were discouraged), "reform from above" could never really succeed. The gap between rulers and subjects was still too vast. The ruling classes were still too steeped in mediaeval conceptions of privilege and aristocratic rights. The people were still too weak, leaderless and disunited. Many more years of bloodshed and upheaval were to follow before Spain could even begin to become a modern European nation.

Under the early Bourbon kings, French advisers and family ties with the French royal family strengthened Spain's relations with her northern neighbour. A more practical reason for contact and collaboration was an identity of interest which the two nations found in their hostility to England. British sea power and British expansion overseas were a continual threat to the Spanish Empire and to Spain's transatlantic trade. When the North American colonies declared their independence from Britain, both Spain and France intervened to help them. It was a short-sighted move. In South America, not many years later, the roles were reversed at Spain's expense, when Britain gave her encouragement to the leaders of the independence movements there.

Meanwhile, the French revolution caused a sudden reversal of Spanish policy in Europe. Royalist and Catholic Spain was outraged by the overthrow of the French Bourbons and attacks on the Church, and hastened to join the fist coalition against Republican France in 1793. But her military efforts were so ineffective that, after a disastrous defeat, she was compelled once again (and on much worse terms than before) to take up arms against Britain at France's side. Again she was defeated. Jervis's victory at St. Vincent temporarily lost her her revenue from overseas. A few years later, hoping finally to consolidate French control, Napoleon invaded Spain, expelled the Bourbon King, and put his own brother Joseph on the Spanish throne.

Then began the first modern Spanish revolution. The people of Spain—or rather, the peoples of the various component parts of Spain—rose against the invader in a new war of liberation. In 1810 the first united Parliament met. It worked out a modern Spanish constitution. Though in many ways an unpractical expression of French revolutionary principles, this constitution is important because it sought, for the first time, to deprive the King of personal power, to exclude the Church from government, and to secure representative elections. But the various local leaders, though inspired by high ideals, suffered from inexperience and lack of unity. Two years later the effective military liberation of Spain began with the help of British forces under Wellington.

The expulsion of Napoleon's armies in 1814 was followed by the restoration of the Spanish Bourbons, and the King promptly rejected the new constitution. With the support of the Church and army, Spain returned again to royal absolutism. But the war of liberation had left deep marks. It had taught the people that they could do without a King. It had restored the lost tradition of parliamentary government. It had spread new democratic ideas throughout the country. Yet it was to take more than another hundred years before all these things were to achieve even temporary realization. The 19th century in Spain is one more chapter of upheaval, revolution and oppression.

When people in Britain watch political struggles in other countries they are sometimes apt to forget their own upheavals in the past. Troubled though Spain had been in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, she had, in fact, spent only half as many years in civil war as England and France. In the 19th century, however, when those two countries were making steady progress towards a democratic way of life, Spain began a new period of desperate civil wars. In other ways, too, these hundred years made sad comparison with what was happening abroad. Western Europe was passing through industrial revolution, but Spain was beset with the crying need for agricultural reforms—reforms which have not yet taken place. While Britain and other European nations were consolidating new colonial Empires, Spain's old Empire was finally lost. Still today, Spain is struggling with many problems, which were solved by her neighbours a hundred years ago.

Not long after the restoration of the Bourbon King, his despotic methods and the incompetence of his advisers provoked a revolution. It was started by an army mutiny in Cadiz, where liberal officers found a ready response from troops weary of long and unsuccessful campaigns against insurgent forces in the Spanish Empire. By now the old monarchy had been restored in France, and once again French intervention saved the Spanish King. But a new division of political forces was growing up in Spain. On the one side were all those—including important sections of the army—who had been affected by the new political currents that had been sweeping Europe. "Liberal" ideas had penetrated Spain, and "liberal" leaders had started to emerge. On the other side were all the old traditional forces of reaction: the King, the court, the landed aristocracy and the Church. An open clash between them was provoked by a dispute about the royal succession in 1834.

The first Carlist war, which lasted for six years, though theoretically a dynastic feud between the dead King's brother (Don Carlos) and his widow, was in fact a political struggle between left and right. That the Queen-Mother should have become a leader of progressive forces was an accident for which she herself was not responsible, and which she certainly resented. But her victory did mean the adoption of a more progressive constitution in 1845, a number of other important reforms and the secularization of monastic lands.

Attacks on the great estates forced the Church, itself the largest Spanish landowner, into particularly firm alliance with the landowning class, and after the defeat of the Carlists—whom it supported—it became all the more closely identified with the forces of reaction throughout Spain. Its spiritual and political influence was still very great, and its material power enormous. At the beginning of the 19th century, including monks, nuns and secular clergy, there were no fewer than 143,398 ecclesiastics in the country. In Italy, at the same period, the proportion of ecclesiastics to laymen was as only half as much. With 3,250,000 acres of agri-cultural land and capital in real estate, the Church derived an annual income, which, with donations, totalled the equivalent of £26,000,000. It is no mere slogan, therefore, to talk of the interest which the Church had in maintaining the social status quo. From now on politics and religion became so fatally entangled that in most parts of Spain they have never yet been separated.

After a temporary lull, the years that followed the first Carlist war saw ever greater confusion inside Spain. Military plots and risings followed one another in monotonous succession. Except for a brief (and moderately successful) operation in Morocco, the Spanish generals devoted their main energies to interfering in political affairs. Meanwhile, intrigues at court were becoming a European scandal. In 1868 a naval mutiny was the signal for a general revolution, and when the Queen fled a long search began for a monarch to take her place. The constitution by which he was to rule was drawn up by Parliament in 1869, and was a model of liberal reform. But when the new King—an Italian Prince—was finally elected and arrived in Spain, his reign was brief and chaotic, and after only three years he found an excuse to abdicate. The vacancy he left behind him was filled by the first Spanish Republic in 1873.

That Republic, which was suppressed by a general before the year was out, had been proclaimed by a parliament that was still fundamentally monarchist in outlook, and was split over the question of decentralization. But its chief supporters in the country were the champions of federalism and local autonomy, who became impatient of parliamentary delays. They proceeded to put their theories into practice. Many parts of Spain assumed their virtual independence. In the south-east all but one of the cities from Valencia to Seville became "independent cantons", and acknowledged no central authority above them.

Meanwhile, the Carlists, whose main recruiting grounds were in Navarre, again rallied. In Madrid three Presidents succeeded one another in and out of office, and Ministers were changing places almost daily, until the military finally took control. In December 1874 a Brigade of troops proclaimed the restoration of the Bourbons, and twelve days later Alphonso XII landed in Barcelona. In two years more the last Carlist strongholds had surrendered, and Spain was again at peace.

The new constitution, which was adopted in 1876, was a compromise between the two earlier constitutions of 1845 (adopted after the first Carlist war) and 1869 (framed after the revolution which led to the first Republic). It was followed by a period of alternate conservative and liberal governments, whose terms of office were determined largely by the palace, and whose supporters in Parliament mostly owed their seats to managed elections, but which did give Spain a few much-needed years of relative internal peace. They were disturbed, however, by a series of revolts in Cuba which culminated in war with the United States, and the loss of Spain's last transatlantic and Pacific possessions in 1898.

With the exception of Morocco, Spain was now left with no important overseas commitments. Her Government could devote its entire attention to domestic problems. There were many that were pressing. One of the most immediate was the need for legislation to curtail the glowing wealth of the Church, which was becoming a formidable capitalist organization, and reaping enormous benefits from its exemptions from taxation. But legislation with this aim aroused such violent opposition from bishops and clergy that its adoption was long delayed.

Meanwhile, with the development of industrialization (particularly in Catalonia, the Basque country and Asturias), the emergence of an urban proletariat, and the spread of socialism and other new ideas, industrial and political unrest was growing. For the first time in their history, the working people of Spain were beginning to become a power in the country. For them, sham democracy was not enough. "Constitutional government", which depended on palace intrigue, faked elections, intimidation from the array and pressure from the Church, was out of date.

The first big popular explosion (the forerunner of many more) took place in Barcelona, after a minor military disaster in Morocco in 1909. The immediate cause was a call-up of Catalan reservists. The result was chaos. In five days of mob rule 22 churches and 34 convents were burned down and scenes of extraordinary ferocity took place; 175 workers were shot in the city streets when the Government regained control, and executions continued for many weeks. This revolt was a sudden episode, and order was soon restored. Bill it served to illustrate the intensity of the fury of the working people against the Army, Government and Church.

Neutrality in the First World War—a neutrality which did not prevent the despatch of war material abroad —did something to revive prosperity in Spain. The nation's sympathies in the conflict were split between the Church, Army, bureaucracy and upper classes, who were mostly pro-German, and the "liberals", intellectuals, traders and working class—and the Basque and Catalan autonomists—who were pro-ally. Towards the end of the war political unrest increased. During a new period of strikes, assassinations, repression and intrigue, it became clear that sooner or later the existing régime must finally succumb to one or other of the forces striving to take power: the republicans and socialists on the one side; or the army, with its military defence committees, organized throughout the country, on the other.

In 1921 a new military disaster in Morocco, for which, this time, the King himself was partly responsible, provoked a widespread demand for public investigation. In the same year there had been new and violent troubles in Catalonia, and general unrest throughout the country. Two years later, just when Parliament had completed a second and fuII enquiry in the Morocco defeat (the first had suppressed many of the facts) and was preparing to publish its report, the Military Governor of Catalonia, General Primo de Rivera, staged a coup d’état. With the King's approval, and with a directorate of generals to advise him, he became the sole Minister of Spain.

The dictatorship—sometimes compared with Kemal Ataturk's régime in Turkey—was absolute, and at first depended entirely on the army. An early act was an official Visit to Italy in 1923 with King Alfonso, who hastened to express his admiration of the fascist State, and to offer to the Pope the troops of Spain in any new crusade the Vatican might plan. In Morocco, in co-operation with the French, native revolts were finally suppressed, and the pacification of the country was completed by 1927.

At home, grandiose schemes of public works were started. The Military Directorate, through which the dictator first governed, lasted until 1925, when he replaced it with a cabinet of civilians. But effective power remained throughout in the hands of the armed forces, and officers everywhere controlled the civil administration. Gradually the dictatorship earned the opposition of all civilian classes. The landowning aristocracy was economically protected, but resented its loss of political power. No attempt was made to tackle the agrarian problem, and the peasants remained oppressed and sullen. The middle class was angered by increasing taxation aimed at industry and commerce, and the dictator (despite considerable efforts) never won the sympathy of the urban working class. The King, too, began to lose faith in his dictator. The first plot—which quickly failed—was organized by an ill-assorted group of disgruntled generals, ousted politicians and demagogues in 1926. Apparently it had the King's support. But as opposition mounted, it became clear that though the Monarchy could not survive with the help of the dictator, without him it was lost. Early in 1930 Primo de Rivera made a last appeal to those who had helped him into power. Spain's military leaders did not respond. He at once resigned and went abroad. At the end of a year of confusion, municipal elections were held throughout Spain. The result was a great victory for the Republican parties. King Alphonso left the country, and in April 1931 the second Spanish Republic was proclaimed.

4. UNITY AND AUTONOMY»top

SOME pages back I noted Spain's geographical isolation from her continental neighbour France. It is geography, too, which largely accounts for what its opponents often inaccurately call "separatism" inside Spain. The Spanish peninsula is an area of great variety of climate, fertility and landscape. At the same time, natural barriers—mountain ranges and semi-desert plains—isolate one region from the next. Modern communications overcame the geographical division of the country, but they cannot overcome the historical and political division which geography has caused.

The struggle between Centralism and local Nationalism, which has persisted since the expulsion of the Moors, might perhaps have been settled centuries ago if the unity of the Crown and of the Church had been accompanied by the unification of popular institutions. Local democracy has very deep roots in the Spanish cities and provinces. But Spain, a collection of originally independent kingdoms, was unified only from above. There was no corresponding unification at the local level. Subjects of the Crown remained citizens of Navarre or Castile or Catalonia. One by one, as Madrid imposed its power upon them, the old kingdoms and the old municipalities lost their traditional local rights. But there was no fundamental union. The first united Parliament did not meet until 1810—in the middle of a revolution. That one fact is symptomatic of the process as a whole.

To the absence of institutional and political unity was added maladministration from the centre. The natural centre for the Government of a single Spain is obviously in New Castile. But the uplands of Castile are, by their very situation, backward and remote from the centres of development and contact with the outside world. The constant feeling that Madrid mishandled and misunderstood their problems was yet another reason for the centrifugal tendencies of the lands she ruled.

So it was that the process of disintegration, that has overtaken Spain at every moment of upheaval since her liberation from the Moors, was as much a reaction against bad and ununderstanding Government as the expression of a real desire for independence. No sensible person would today suggest that Spain can be anything but one economic unit. Politically as well, a great many of the functions of government must clearly belong to the nation as a whole. But there are also local problems which could most efficiently be settled on a local basis. There is, too, in several parts of Spain, a real feeling of individual national consciousness, which repression only makes more bitter and determined, but which reasonable gratification could make into a source of unity and strength.

There are today three areas where effective autonomist movements exist: the Basque country ("Euzkadi"), Catalonia and Galicia. Of these Galicia is the least prominent because the autonomist movement there has only re-emerged in very recent years. Galicians speak their own dialect (very like Portuguese), and have a culture of their own. But their chief problems are isolation, meagre resources, and a very low standard of living. Euzkadi and Catalonia, in contrast, are the two most prosperous, highly developed, and fully industrialized regions in the country. They are, in short, "the Irish problem in reverse". With about 11 per cent of the total Population of Spain, Catalonia today pays over 40 per cent of the receipts of the Spanish exchequer. The fact that the greater prosperity of the Basques and the Catalans has constantly provoked the envy of Castile, whom they accuse of draining their wealth and giving virtually nothing in return, is one of the reasons for their determination to control their own destinies in future.

There are many others. For example, the Basques can recall that their original, and complete, independence was only lost because freely negotiated agreements were systematically violated by Spanish kings. And they can claim that racially they are not related to the Spaniards (in this their ancient language and their early history bear them out), and that almost all their local problems are different, and sometimes the opposite, of those of Spain. Whereas in Castile or Andalusia the great agrarian problem is the big estate, the danger for the Basques is that the peasants’ holdings will become too small. Industrialization in Euzkadi has already been achieved. Their natural resources are fully exploited with up-to-date techniques. From the earliest times a nation of many sailors (they signed with Edward III of England the first treaty establishing the freedom of the seas), they had had constant contacts with the outside world. Even the Church in Euzkadi is different from the Church elsewhere. Relatively free from reactionary political affiliations, with a high general standard of culture and close ties with the working people, the Basque clergy are an example to their colleagues in other parts of Spain. Socially, class divisions are far less acute. By some accident of history or necessity of geography—though the Basques would claim it as proof of their natural democratic instincts—feudalism never fully imposed itself upon their people. To this day an atmosphere of solidarity—social and political—has lasted. It may do much to ensure easy transition in the future.

Catalonia, on the other hand, is a country where oppression has provoked violent extremes. By language and culture she was originally an extension of southern France rather than part of Spain. In the 14th century she built up an extensive Mediterranean empire of her own, and her merchant seamen compiled Europe's first code of maritime law. Prosperous as a trading nation, she had few contacts in mediaeval times with her semi-pastoral neighbours on the interior plateaux. But when she was united under the crown of Castile early in the 15th century her first decline began. The fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453 had made the Mediterranean unsafe for Christian ships, and wrecked her maritime trade. With the discovery of America the primacy of Spanish ports passed from Barcelona to Seville. Catalans were excluded from transatlantic commerce. At the same time extensive peasant troubles did temporary damage to her agriculture.

But it was not till the 17th century, when royal efforts at centralization became stronger, that the first big Catalan revolts began. In 1640, while Spain was in the middle of a war with France, the Catalans rebelled and placed themselves under the protection of the French king. This was the signal for a number of other provincial risings, in one of which Portugal won her final independence. Barcelona only submitted after 12 years to the King's forces, and Catalan guerillas in the countryside kept up the fight for seven more. Forty years later—during the War of the Spanish Succession—the Catalans rebelled again. After a fearful siege of Barcelona the King regained control in 1714, abolished the remains of Catalonia's political independence, closed the Catalan universities and started a new period of repression.

At the beginning of the 19th century the Peninsula War was the signal for a general disintegration of Spain. Until the arrival of British forces under Wellington, operations against the French invaders were carried out on a regional and local basis, and some 20 impromptu committees in various parts of the country declared their independence. Catalonia was occupied by French troops for five years.

There was another Catalan revolt in 1823, and then, under a "liberal" Government in Madrid, a further period of repression, in which Catalonia lost her few surviving local rights—her commercial and penal law, her special tribunals, the use of her language in schools, her coinage, and her local administration. But this was only the signal for a new revival: particularly a linguistic and cultural revival. The Catalan nationalist movement in its present form first began to organize itself about a hundred years ago.

At first it was not predominantly a movement of the left. The big Barcelona rising against the Central Government in 1842 was organized by a combination of factory owners and workers. As industrialization increased the Catalan industrialists and the prosperous bourgeoisie took the lead against the centralism of Madrid. Allied to them at first were the Carlists, who, though reactionary and pro-clerical, also stood for local liberties and interests. After the second Carlist war ended in 1876, the Church herself still supported the autonomists in both Catalonia and Euzkadi. But as the industrial proletariat grew stronger, and as wave after wave of terrorism and repression swept the country in the early 1900s, the leadership of the nationalist movements passed gradually to the people. In 1909 the oppressive policy of the Central Government provoked wild riots which were followed ten years later by the first big general strike. Well organized and relatively peaceful, it paralysed Barcelona and caused the fall of two successive governments in Madrid. This time Government repression was more ferocious than ever before. Upheavals, atrocities and assassinations continued without a pause until 1923, when Primo do Rivera, then Military Governor of Catalonia, made his successful coup d'état.

During his dictatorship, Catalan nationalism was driven deep underground. This, and the declared anti-Catalan sentiments of King Alfonso XIII, made it more than ever republican and left wing. Only after the coming to power of the Republic of 1931, which was actually preceded by the declaration of a Catalan Republic, did Catalonia regain her freedom of expression, her local autonomy, and the right to remember her individuality and her own traditions. The story of the Generalitat of Catalonia, of the autonomous government of Euzkadi, and of how, during the last civil war, the age-old Spanish regionalist tendencies came once again to life, belongs to recent history. But local nationalism and the problems of Catalonia and Euzkadi are not new. They have deep roots in the past. They can never be extinguished by passing wars or military dictators.

5. PRELUDE TO CIVIL WAR»top

THE proclamation of the Second Republic in 1931 marked the final collapse of the 19th-century monarchical setting in which successive Spanish governments, "constitutional" and dictatorial, had followed one another since the first short-lived Republic fell in 1874. During those years the traditional elements in Spanish political life had, one by one, become discredited by abuse. The monarchy had tried to secure its own survival by calling in a military dictator. The dictator had now fallen, and the monarchy, by its association with him, had lost all popular prestige and many of its most powerful friends. The Church, identified with the interests of the ruling class, inextricably mixed in politics, and (with few local exceptions) reactionary to the core, had been a focus of bitter dissension for a hundred years. The army, "the strongest political party in the State", had been responsible for countless risings and rebellions, culminating in the dictatorship which had just surrendered to universal disapproval, and from which the generals themselves had finally withdrawn support. Even the memory of parliamentary government, with its faked elections, its intrigue, and its "management" behind the scenes, had become the target of mockery and disillusion.

In this atmosphere of past failures, the new Republic came to power. It inherited all the old problems still unsolved. Smouldering under centralist repression, the separatist movements were very much alive. In the countryside the agrarian problem had become, if possible, more acute than ever, and the industrial areas were full of discontent. Economically, the country was unstable. After seven years of military rule the administrative machine was inefficient and corrupt.

This was the moment for swift and sweeping changes. The moment to show the Spanish people that the oppression and reaction which for centuries they had associated with the rule of kings had really ended. That government by small privileged minorities was finished, and that the Spain of the future belonged to them.

But the men who first took over when the King left Spain were hardly the natural leaders of a new era of reform. They had no great force of popular enthusiasm to support them. They saw the end of the dictatorship and monarchy more as an expression of general dissatisfaction at the personal incompetence and failure of the dictator and the King, than as a conscious demand for progressive changes in the future. They could claim that the revolution itself had been made not by the nation as a whole, but by the votes of the middle class and some of the workers of the towns. The people of Spain, they thought, had still not begun in earnest the battle for their freedom and their rights.

It was significant that in the very early days even the Church was not unsympathetic to the new Republic, and shortly before the change took place a number of the political leaders of the old ruling class announced their conversion to its cause. It was from their ranks that the first President, Alcala Zamora, was chosen.

The elections which followed in April 1931, however, showed a great landslide. It was the first unchallengeable expression of the desire for something new. Despite the influence of landlords and the management of voting results in country districts—where hatred of the old régime was most justified and most bitter—but which none the less often returned candidates of the right, the republicans and their socialist allies were returned with an immense majority. Only 19 confirmed monarchists were elected to the new Constituent Assembly.

The first Government was predominantly liberal, and included three socialist ministers. For months the Assembly worked on the new Spanish constitution. As finally adopted it represented a great break with the past. "Spain is a democratic republic of workers of all classes …" it began. Its clauses went on to grant universal suffrage, a single legislative chamber, the separation of Church and State, freedom of religion, control of all religious orders, and a ban on their holding more property than they needed for their own subsistence. There was also a provision for the granting of statutes of autonomy to such groups of provinces as might apply, and a definition of the powers of central and local governments. Catalonia became an autonomous Generalitat, with its own President and Parliament, in April 1931. But though the Basques asked—in a local plebiscite—for their autonomy in 1933, it was not finally granted to them until after the civil war began.

The early years of the Republic were beset with troubles. One fundamental cause was the failure of the new régime to press ahead with agrarian reform. In three years only just over 12,000 peasants were given land, out of two and a half million landless. The secularization of the Church was certainly also an urgent problem, but while the Government became deeply involved in bitter disputes about this subject, the great mass of peasants were left in their old conditions of de facto serfdom. Peasant revolts broke out. They were preceded by a series of local strikes, anarchist risings, and a general strike in Barcelona. By 1933, when a rebellion of land-hungry peasants was repressed with particular ferocity by Government police, the new Republic had already lost much of the sympathy of "all the workers" whom it claimed to represent.

The clean-up of the army, too, was ineffective. In the early days of the Republic large numbers of redundant and right-wing officers had been retired—"honourably", and well pensioned. But already, in 1932, the first military revolt broke out in Seville. Its leader was General Sanjurjo, who, had at first been entrusted by the Republic with the maintenance of order. His revolt, inspired by the monarchists, was suppressed. He himself was sentenced to life imprisonment. A little later he was exiled on parole.

So in the elections of November 1933 a right-wing coalition against the socialists and left republicans came to power. The new Government was in the hands of monarchists and Catholic agrarians. That was the end of the period of attempted "liberal" progress. It had failed, partly because popular forces were not yet ready or united, partly because the strongest social and political element was still the old land-owning aristocracy, which had successfully prevented its power being broken by radical agrarian reform. In those times strong and far-sighted democratic leaders were desperately needed. Years of dictatorship and repression had made such leaders rare.

Under the new Government another period of repression for the peasants and the urban proletariat began. In February 1934 28,000 peasants were dispossessed from land which they had taken, and strikes flared up in Saragossa and Madrid. At the end of that year Spain's modern fascist party, the Falange, was first formed. Its leaders were the ex-dictator Primo de Rivera’s son, and young landowners from Andalusia and Castile. At the same time the Government moved still further to the right, and a ministry including new clerical and reactionary ministers took office in October. Uproar throughout the country followed, and the bourgeoisie and proletariat found themselves again united against the new régime. By now the parties of the left and the trade unions were convinced that the monarchists and the right wing were preparing to overthrow the Republic. There was another general strike. The Catalan Generalitat severed connection with Madrid. In Asturias the miners revolted and held their local capital, Oviedo, for nine days. Order was eventually restored—in Asturias only with the help of Moorish troops—but it cost the Left thousands of dead and wounded, and over 35,000 political prisoners.

Disunion then arose among the Government parties, and the Government resigned. In October 1934 it was replaced by a Cabinet still further to the Right. Among its junior ministers was General Franco, Under-Secretary for War. For the next 16 months the Spanish right was virtually unopposed—except by smouldering popular discontent throughout the country. Eventually, after a further Cabinet change, the President of the Republic granted a decree of dissolution, and in February 1936 the last general election took place.

The parties of the right formed an "anti-Marxist" alliance. The moderate Republicans and the left united in the "popular front". They won a great electoral triumph, for which the savage repression of the previous Governments, from 1934 onwards, was at least partly responsible. In the new Parliament the right was represented by 152 members, the centre by 62, and the popular front by 258. The leader of a strong republican group of deputies, Don Manuel Azaňa, became Prime Minister (for the second time) in a Government composed of members of the two main moderate republican groups. In May, at the demand of Parliament, President Zamora was removed and Azaňa took his place. The new Government was led by the head of another of the moderate republican groups. The socialists and other left-wing parties were not asked to join the Government until after civil war had broken out.

Meanwhile, disorder was rife throughout the country. The election itself had taken place in comparative calm. Now, however, riots, strikes and assassinations followed one another to a climax. As the right became more and more aggressive, so violence from the left increased. On July 13th Calvo Sotelo, a spokesman of the right in Parliament, and a former minister of the dictator Primo de Rivera, was assassinated—apparently as a reprisal for the murder of a police officer the day before. Five days later the army of Morocco revolted under General Franco, and the Spanish Civil War had begun.

The five years of the second Republic were a happy period for Spain. They culminated in disturbance and military revolt. The end of the monarchy had not led to that period of peace and progress for which the Spanish people had waited for so long. Its failures were the result of many causes. At the beginning the Republic was divided against itself. Some of its early leaders had no real faith in its institutions or understanding of its purpose. The great power of the representatives of the old régime was never effectively broken. Because of this, long-waited reforms were endlessly delayed. In their impatience for liberation from the oppression of the past, the workers, and above all the peasants, were continually frustrated. When, at last, their own chosen leaders came to power with a great majority over the parties of the right, they were at once challenged with threats of rebellion and revolt. While the army planned and plotted, its political allies helped to work up violence and disorder throughout the country. They knew that this was the moment when, unless they struck, the people of Spain would take their future into their own hands. They knew that no intrigues, no "management", no peaceful efforts could any longer save them and the old order which they represented.

For centuries Spain has been a country of sharp divisions. Never was the division clearer than in 1936. On the one side the Republic, the Government, and the Spanish people who had put that Government in power. On the other, all the old forces of privilege and reaction: aristocracy, landowners, Church, and, above all, the army. Without the army, the rest were helpless. But the army, "fully conscious of its historical mission towards Spain", was ready, with powerful foreign allies, to turn against its enemy, the Spanish people. For 32 ½ months it fought them. In the end it won.

6. THE MILITARY CAMPAIGN»top

ON July 17th, 1936, the military garrisons of Melilla and Ceuta, in Spanish Morocco, revolted. General Franco, after ensuring the rebellion of the troops under his own command in the Canary Islands, flew to North Africa to take control. Next day all the large garrisons on the mainland joined the revolt, and the first insurgent detachments from Morocco landed at Cadiz. By the end of the week the military rebels controlled most of the big cities of mainland Spain, except those on the east and north coasts and Madrid. In Barcelona the local commander had remained loyal to the Government, and with the help of civilians, Civil Guards and Shock Police, the garrison troops were overcome before their officers could launch a concerted offensive. In the capital the workers alone, armed by the Government, overcame the troops in a short and violent struggle. In the north, only Oviedo was in rebel hands, and there the troops were besieged by the local population.

Despite many warnings, the Government was apparently taken by surprise. It had not believed in an army insurrection, had made no preparations to meet it, and only became convinced of its seriousness after several days. Then it found itself faced with a formidable problem. To suppress a large number of geographically separate revolts before the rebel armies could unite, it had virtually no organized forces at its disposal. Almost every Spanish officer who found himself free to do so had joined the rebels. Those who remained comprised 25 trained staff officers, and about 500 regimental officers of the various arms of the service. The navy was divided. Loyal crews had overthrown their officers on a number of vessels, but Spain's only battleship, two new cruisers, and several smaller craft, as well as the naval bases at Ferrol and Cadiz, were taking rebel orders. In North Africa General Franco had at his disposal 11,000 well-trained Moorish troops and the Spanish Foreign Legion, 5,000 strong. The air force was divided, and the Republic had no effective aircraft. Of the police forces, almost all the 6,500 newly-formed Shock Police remained loyal, but the 34,000 Civil Guards joined the rebels, except those in Barcelona. The bulk of equipment and military stores was naturally in army hands.